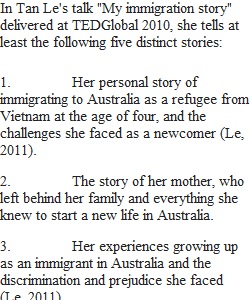

Q SESSION TWO Tell a Good Story To listen to a recording of this lecture and chapter reading, click the link below WRAC 101 Section 2.m4a We all have a good story to tell; but not all of us are skilled at telling a good story. This takes practice. It requires attention to presentation and the ability to coherently link one idea to the next. In this section, we are going to consider how to make those links by thinking about the ideas we are sharing as we move through a story. First, you need to decide what central idea you want to communicate to an audience. Then, you need to communicate that idea, a piece at a time, throughout an entire story. Take a moment and think about a story you recently told a friend. For instance, maybe you told them about an argument you had with a sibling, or how you meant someone new and you’d really like to go out with them, or you gave them a play-by-play story on how you beat the next level of a video game. Did you have to stop and go back and fill in missed details? Did they ask you questions about things that were unclear? Did you tell the story well? Or poorly? Missed details, lack of clarity, and needing to answer a listener’s questions are all normal parts of telling a story when face-to-face. And, when face-to-face, these things are easy to remedy. But, when writing a story, you need to get all of those items situated correctly. That’s why it’s important to think through each point you wish to make ahead of time and organize a thoughline (as will be discussed in the Ted Talk chapter below). First, however, watch this Ted Talk video titled My Immigrant Story. While doing so, follow each of Tan Le’s points to discover her throughline. What is Le’s main idea and how does she carry it, point-by-point, through the talk. You will answer questions about this later. If you have trouble understanding the speaker, be sure to turn on subtitles by choosing the little dialogue box and then choosing the language you want displayed. After watching the video, read this chapter from the book Ted Talks: The Official Guide to Public Speaking by Chris Anderson. THE THROUGHLINE What’s the Point? “It happens way too often: you’re sitting there in the audience, listening to someone talk, and you know that there is a better and great talk in that person, it’s just not the talk he’s giving.” That’s TED’s Bruno Giussani again, a man who cannot stand seeing potentially great speakers blow their opportunity. The point of a talk is . . . to say something meaningful. But it’s amazing how many talks never quite do that. There are lots of spoken sentences, to be sure. But somehow they leave the audience with nothing they can hold on to. Beautiful slides and a charismatic stage presence are all very well, but if there’s no real takeaway, all the speaker has done—at best—is to entertain. The number-one reason for this tragedy is that the speaker never had a proper plan for the talk as a whole. The talk may have been planned bullet point by bullet point, or even sentence by sentence, but no time was actually spent on tis overall arc. There’s a helpful word used to analyze plays, movies, and novels; it applies to talks too. It is the throughline, the connecting theme that ties together each narrative element. Every talk should have one. Since your goal is to construct something wondrous inside your listeners’ minds, you can think of the throughline as a strong cord or rope, onto which you will attach all the elements that are part of the idea you’re building. This doesn’t mean every talk can only cover one topic, tell a single story, or just proceed in one direction without diversions. Not at all. It just means that all the pieces need to connect. Here’s the start of a talk thrown together without a throughline. “I want to share with you some experiences I had during my recent trip to Cape Town, and then make a few observations about life on the road . . .” Compare that with: “On my recent trip to Cape Town, I learned something new about strangers—when you can trust them, and when you definitely can’t. Let me share with you two very different experiences I had . . .” The first setup might work for your family. But the second, with its throughline visible from the get-go, is far more enticing to the general audience. A good exercise is to try to encapsulate your throughline in no more than fifteen words. And those fifteen words need to provide robust content. It’s not enough to think of your goal as, “I want to inspire the audience” or “I want to win support for my work.” It has to be more focused than that. What is the precise idea you want to build inside your listeners? What is their takeaway? It’s also important not to have a throughline that’s too predictable or banal, such as “the importance of hard word” or “the four main projects I’ve been working on” Zzzzz . . . You can do better! Here are the throughlines of some popular TED Talks. Notice that there’s an unexpectedness incorporated into each of them. • More choice actually makes us less happy. • Vulnerability is something to be treasured, not hidden from. • Education’s potential is transformed if you focus on the amazing (and hilarious) creativity of kids. • With body language, you can fake it till you become it. • A history of the universe in 18 minutes shows a path from chaos to order. • Terrible city flags can reveal surprising design secrets. • A ski trek to the South Pole threatened my life and overturned my sense of purpose. • Let’s bring on the quiet revolution—a world redesigned for introverts. • The combination of three simple technologies creates a mind-blowing sixth sense. • Online videos can humanize the classroom and revolutionize education. Barry Schwartz, whose talk is the first one in the list above, on the paradox of choice, is a big believer in the importance of a throughline: Many speakers have fallen in love with their ideas and find it hard to imagine what is complicated about them to people who are not already immersed. The key is to present just one idea—as thoroughly and completely as you can in the limited time period. What is it that you want your audience to have an unambiguous understanding of after you’re done? The last throughline in the list above is from education reformer Salman Khan. He told me: There were a lot of really interesting things that Khan Academy had done, but that felt too self-serving. I wanted to share ideas that are bigger, ideas like mastery-based learning and humanizing class time by removing lectures. My advice to speakers would be to look for single big idea that is larger than you or your organization, but at the same time to leverage your experience to show that it isn’t just empty speculation. You throughline doesn’t have to be as ambitious as those above. But it still should have some kind of intriguing angle. Instead of giving a talk about the importance of hard work, how about speaking on why hard work sometimes fails to achieve true success, and what you can do about that. Instead of planning to speak about the four main projects you’ve recently been working on, how about structuring it around just three of the projects that happen to have a surprising connection? In fact, Robin Murphy had exactly that as her throughline when she came to speak at TEDWomen. Here’s the opening of her talk. Robots are quickly becoming first responders at disaster sites, working alongside humans to aid recovery. The involvement of these sophisticated machines has the potential to transform disaster relief, saving lives and money. I’d like to share with you today three new robots I’ve worked on that demonstrate this. Not every talk has to state its throughline explicitly up front like this. As we’ll see, there are many other ways to intrigue people and invite them to join you on your journey. But when the audience knows where you’re headed, it’s much easier for them to follow. Let’s think once again of a talk as a journey, a journey that the speaker and the audience take together, with the speaker as the guide. But if you, the speaker, want the audience to come with you, you probably need to give them a hint of where you’re going. And then you need to be sure that each step of the journey helps get you there. In the journey metaphor, the throughline traces the path that the journey takes. It ensures that there are no impossible leaps, and that by the end of the talk, the speaker and audience have arrived together at a satisfying destination. Many people approach a talk thinking they will just outline their work or describe their organization or explore an issue. That’s not a great plan. The talk is likely to end up unfocused and without much impact. Bear in mind that a throughline is not the same thing as a topic. Your invitation might seem super-clear. “Dear Mary. We want you to come talk about that new desalination technology you developed.” “Dear John. Could you come tell us the story of your kayaking adventure in Kazakhstan?” But even when the topic is clear, the throughline is worth thinking about. A talk about kayaking could have a throughline based on endurance or group dynamics or the dangers of turbulent river eddies. The desalination talk might have a throughline based on disruptive innovation, or the global water crisis, or the awesomeness of engineering elegance. So how do you figure out your throughline? The first step is to find out as much as you can about the audience. Who are they? How knowledgeable are they? What are their expectations? What do they care about? What have past speakers there spoken about? You can only gift an idea to minds that are ready to receive that type of idea. If you’re going to speak to an audience of taxi drivers in London about the amazingness of a digitally powered sharing economy, it would be helpful to know in advance that their livelihood is being destroyed by Uber. But the biggest obstacle in identifying a throughline is expressed in every speaker’s primal scream: I have far too much to say and not enough time to say it! We hear this one a lot. TED Talks have a maximum time limit of 18 minutes. (Why 18? It’s a short enough to hold people’s attention, including on the Internet, and precise enough to be taken seriously. But it’s also long enough to say something that matters.) Yet most speakers are used to talking for 30 to 40 minutes or longer. They find it really hard to imagine giving a proper talk in such a short period of time. It’s certainly not the case that a shorter talk means shorter preparation time. President Woodrow Wilson was once asked about how long it took him to prepare for a speech. He replied: That depends on the length of the speech. If it is a 10-minute speech it takes me all of two weeks to prepare it; if it is a half-hour speech it takes me a week; if I can talk as long as I want to it requires no preparation at all. I am ready now. It reminds me of the famous quote attributed to a variety of great thinkers and writers: “If I had more time, I would have written a shorter letter.” So let’s accept that creating a great talk to fit a limited time period is going to take real effort. . . Questions for Discussion After watching the video and reading the chapter, answer the following questions in the appropriate section of the Discussion board. • Identify the thoughtline in the presentation. What is Tan Le’s idea and how does she build on this idea throughout the presentation developing a clear path for her audience to follow? First decide what her main idea is and then identify at least three different ways she highlights this idea through her stories. • Identify ALL of the stories Le tells in the talk. There are at least five distinct stories though you may identify others. • Notice that the first and last stories in Le’s talk are about a grandparent. Last week we watched a video in which the speaker started her talk with a personal story before she led us into her research. This week, Le has told us many stories to highlight the importance of resilience through difficult circumstances. She begins with a personal story of her grandfather and ends with a personal story of her grandmother. This should tell us something about how to end an essay. When we end the larger story we are telling in our essay assignments, it is important to bring readers back to the beginning of our larger story, but also to take them to a new place. Tan Le does this be beginning and ending with stories of a grandparent—the beginning and end have this in common. But, then her ending reveals that it is the grandmother or women in her family that are the most resilient—this take the audience to a new place. Write a short paragraph on how are the stories of Le’s grandparents are the same and how are they different? Be specific. What effect did each story have on you personally? After answering these questions, be sure to respond to two of your classmates answers on the Discussion Board.

View Related Questions